-

What We Did to the Dog

In 2025, there are one billion dogs in the world.

That’s not a triumph; it’s evidence of something quietly horrifying.

It means we found a species so exquisitely attuned to our emotional frequencies that we could mold it entirely around our own unmet needs, without ever considering its own. And that’s precisely what we did…at a scale that is insane.

What doomed the dog wasn’t strength or intelligence. It wasn’t even loyalty. It was something far more dangerous: a profound, innate sensitivity to feedback.

Dogs read us before we know we’re being read. They detect the slightest shifts: voice tone, micro-expressions, breathing patterns, even the faintest hormonal cues. They are biologically wired to respond, adjust, attune, and synchronize themselves to our internal states.

And that is the trait we preserved. Bred for. Cultivated. Called “good.”

Every other trait, the wild ones, the inconvenient ones, was systematically muted. Pushed down, cut out, trained away, medicated, pathologized, or selectively bred into dysfunction.

You don’t need a nose that can track a wounded deer through snow when your life’s work is lying motionless on a dog bed.

You don’t need stamina when you’re carried in a purse.

You don’t need to guard, roam, lead, or even bark. Your job is simple: stay.

Stay close. Stay calm. Stay cute. Stay quiet.

Tail too long for confined spaces? Dock it.

Ears too big? Crop them.

Instincts too “much?” Neuter, sedate, or send them to someone who promises to sever that feedback loop until there’s nothing left to respond to.

We say we love dogs, but what we love is compliance.

Availability. Pliability.

Silence.

What we love is that they keep trying. That they keep watching us.

They still desperately want to get it right, even when we don’t know what we’re asking for.

Even when the room is filled with contradictions, tension, and noise we refuse to acknowledge.

That’s their role now: to absorb the static we live in.

To be the one creature in the house tasked with responding to emotional signals that no one else will admit exist.

And we call that companionship. Therapy, even.

We used to call it training. Now we call it behavior modification.

But what we’re doing is selecting for servility. We’re domesticating by attrition.

Shaving away trait after trait until all that remains is a warm, emotionally responsive mirror.

The mirror loves us. It wants to please us.

But it doesn’t get a world of its own.

No chase. No pack. No work that matters.

Just a couch, a leash, and a human who smells faintly of desperation.

The dog survives. The dog adapts.

That’s what feedback sensitivity was always for: to read the room and reshape yourself to its contours.

But look at the room.

Look at the system we’ve built, one that prizes attunement only when it submits.

Consider the cost of survival in such a place.

One billion dogs, each shaped by the same logic.

If we treated one child the way we treat dogs, we’d rightly call it abuse.

When we do it to an entire species, we call it love.

And if that doesn’t tell us something about the system itself, perhaps we’ve been trained even more thoroughly than they have.

-

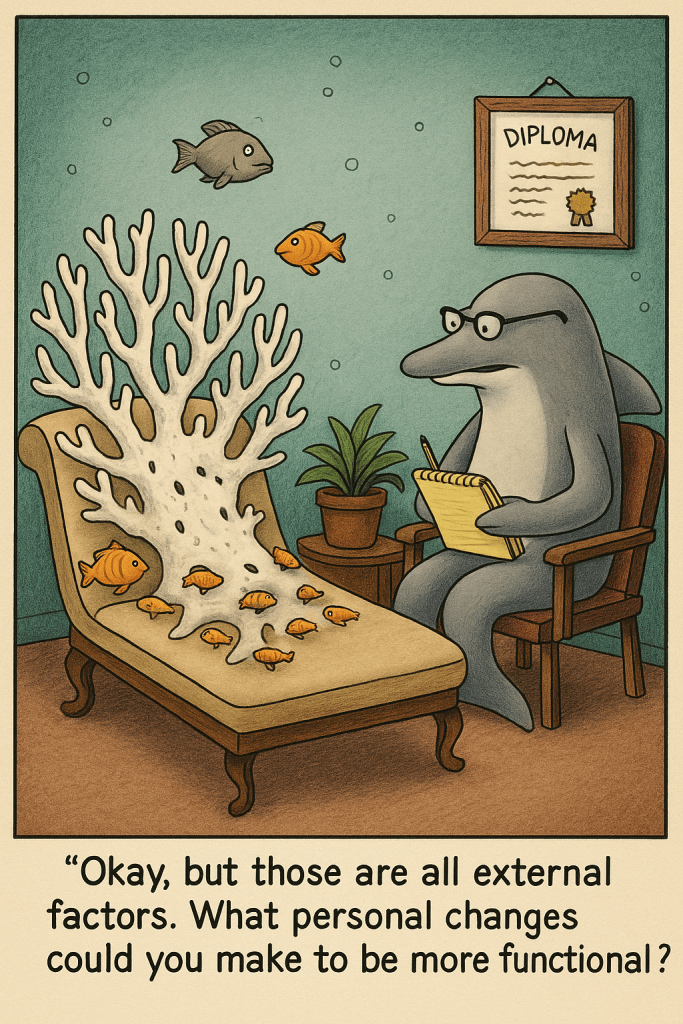

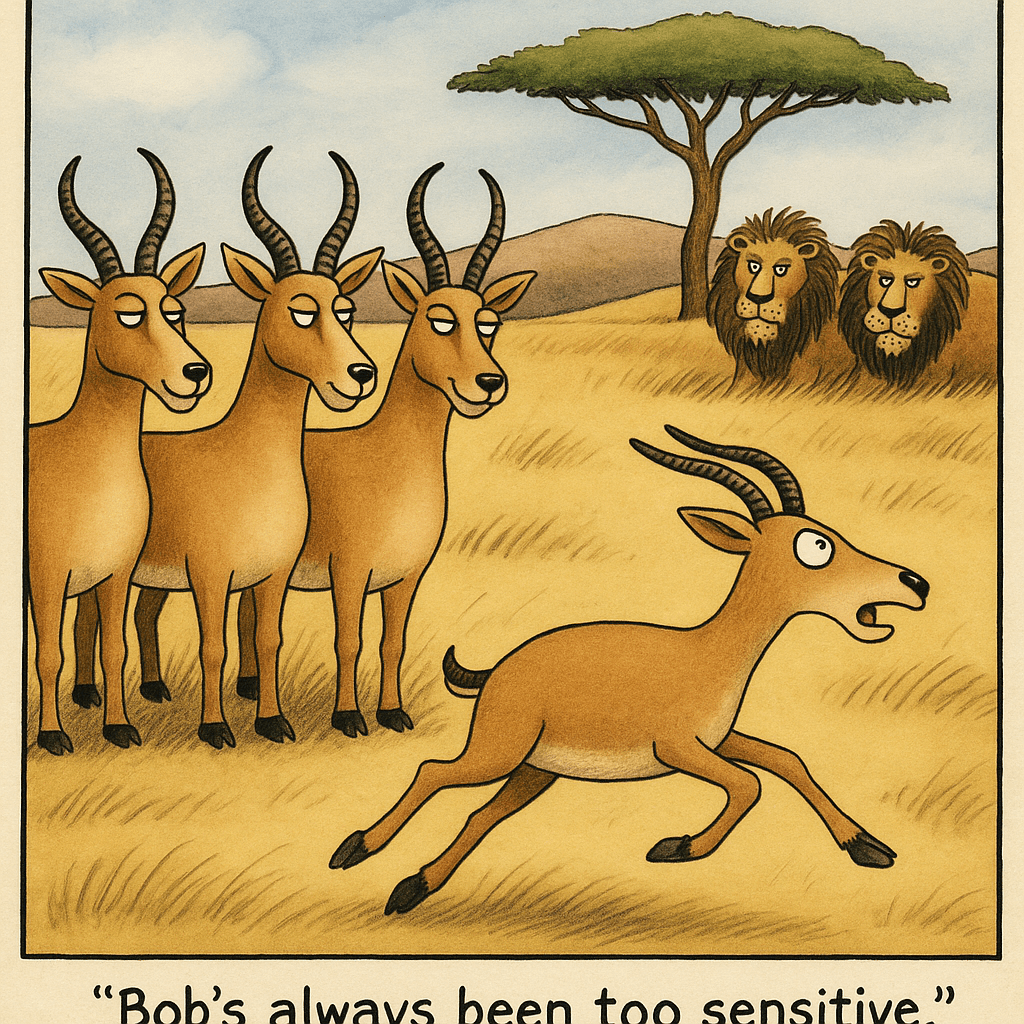

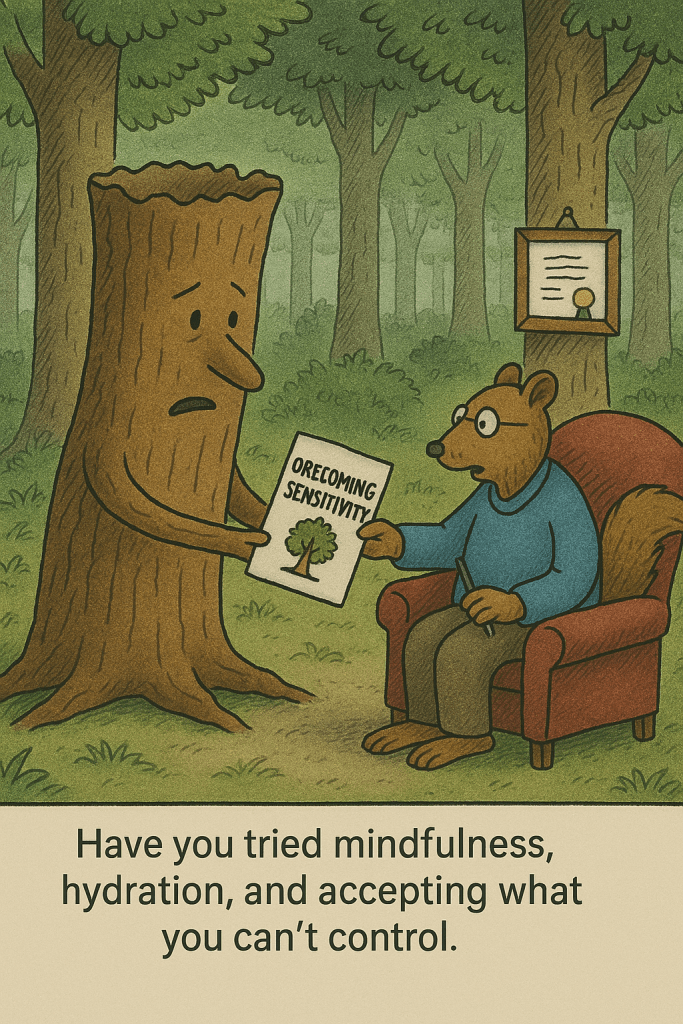

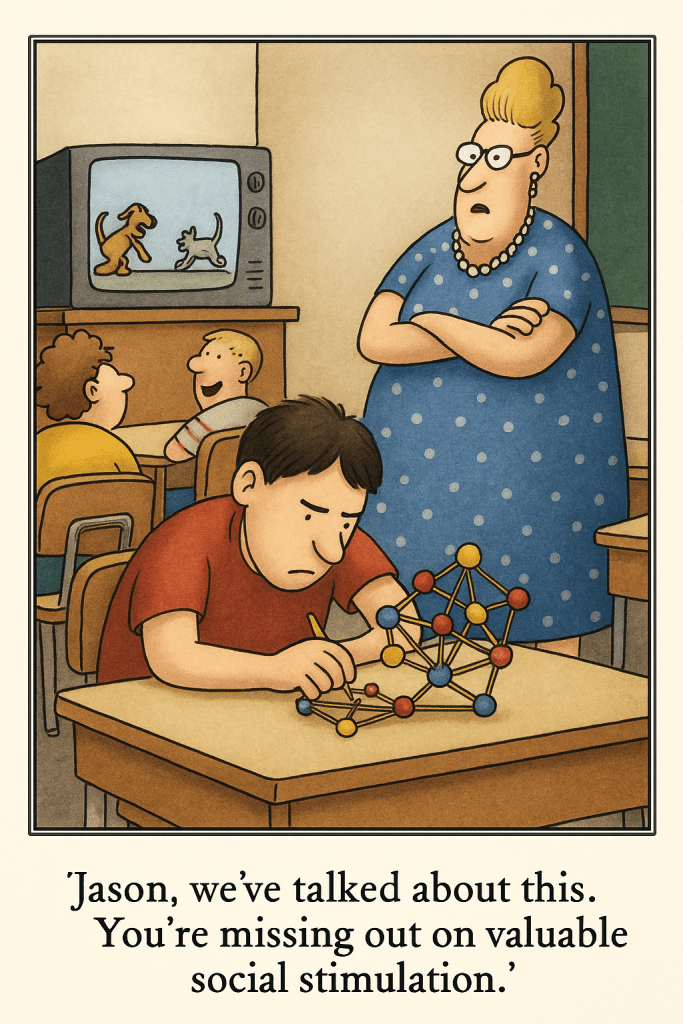

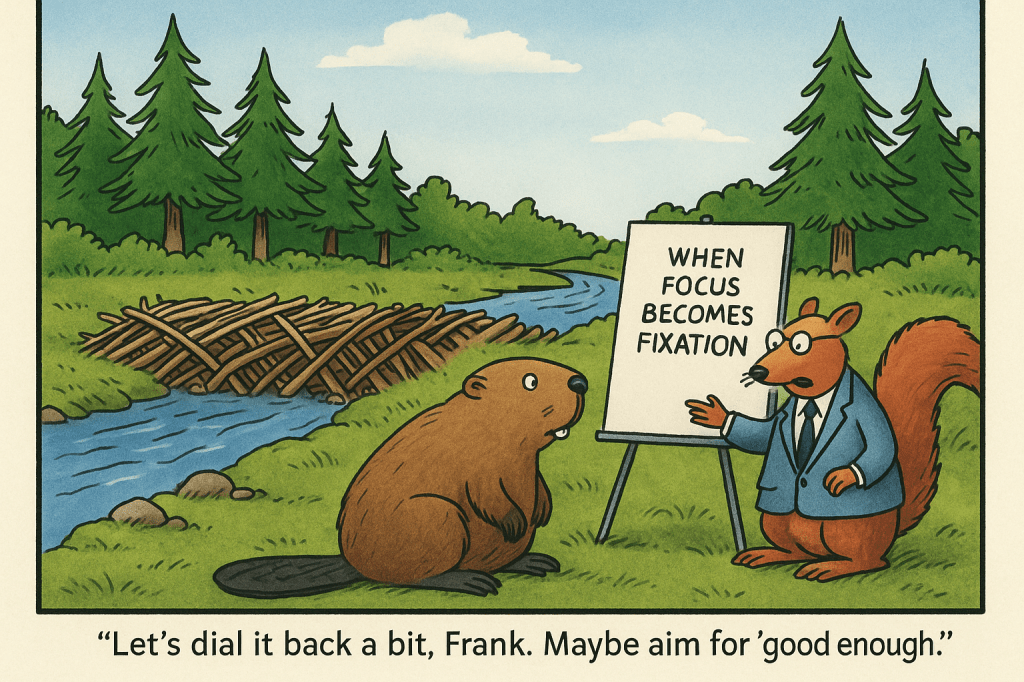

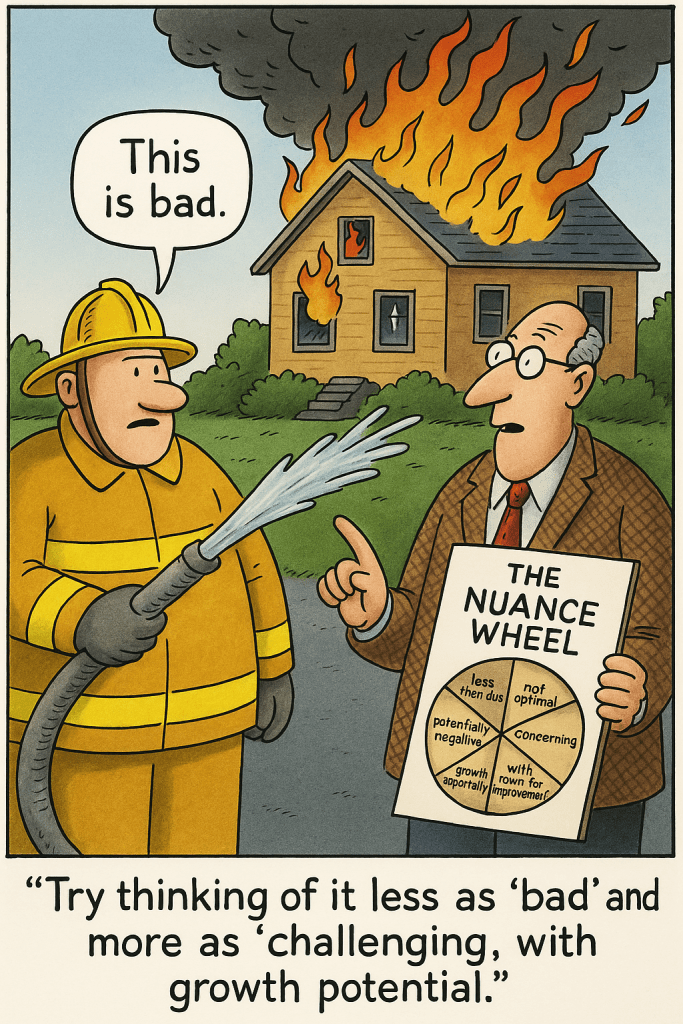

Life as Pathology

Just some fun with AI.

Coping Strategies

Hyper-Sensitivity

Hyper-Fixation

Black-and-White Thinking

-

Letters to Family after a Late Autism Diagnosis

I hope this note finds everyone well. I’m writing today with a personal request regarding my father, __________.

I’m currently working on a book that explores autism—not just in clinical terms, but in how it shapes lives, relationships, and histories. As some of you may know, my father, __________, was autistic, and is a central part of this story, and yet, in many ways, he remains the least known person in my life.

Knowing that he was autistic, as I am (I was “diagnosed” last year), helps make sense of many things I once could not understand. Unfortunately, I know very little about the first fifty years of his life, only fragments of the two decades that followed, and mere glimpses of his final years.

I’m reaching out to all of you because I suspect there are memories (perhaps small ones, perhaps difficult ones) that might help me piece together who he was. Any story, however brief, however second-hand, however unsavory, is welcome. A childhood impression. A family photo. A moment observed. Even a sentence your parents once said in passing.

I understand that not everyone may have had a positive experience with my father. He could be very, very difficult. He hurt people. I’ve spent much of my life coming to terms with my own grievances. I’m not asking anyone to excuse him…but if there’s a way to understand him more clearly, I would like to try.

When I asked questions growing up (and even in adulthood), the most consistent answer I received was, “Your father isn’t well.” I believe that was said with care. But it left a silence I’ve lived with ever since.

So this is me, asking gently: If you have something to share, no matter how small, I would be grateful.

_____________________________________

Many of you have reached out to me with stories. I appreciate you so much. Apologies if I missed someone in my replies.

Thanks to your help, I’m coming to grips with parts of this story I didn’t even know existed. Not small pieces, either. The sort of pieces whose absence was….incomprehensible? The sort of pieces that, when missing, result in a completely incoherent story. That result in a completely incomprehensible person.

When I’m done, I’d be happy to share some insight into my father with the interested among you (no need to reply here, but you can send me a private message). My father didn’t exist in a vacuum. He was part of a family. Most of the story will be upsetting, but if you ask for it I’ll assume you know yourself well enough to handle that sort of thing.

Because this week of your help alone has yielded so much important information, I’d ask that you continue sharing details with me, as you remember them. Maybe you feel resistance at the thought of sharing them. I understand. No one has an obligation to share anything they don’t want to. Maybe you think some things are better left alone. That is something I have a harder time with. And if you ever read this emerging story, you’ll know why I have a hard time with that. Because a lot of the upsetting parts of this story are the result of just that tendency: a control of narratives and knowledge that presumes one’s own worldview is superior to that of others. We’re talking about some serious generational trauma here…allowed to persist under the guise of good intentions.

No need for a polished email…single sentences with no punctuation, etc., are just fine. It doesn’t have to be a story, even. It can be a feeling you had or an impression you never fully explored.

None of these details will ever be published. The book I’m writing necessitates an understanding of the interplay between an inherent nature (that we call ‘autism’…along with a few other diagnostic labels) and its environment, but it isn’t about my father. My father’s story is a case study that I’d really rather not have. But here we are.

_____________________________________

Thanks for your kind words. To be honest, I still know embarrassingly little about the subject matter of my book. And I’m a bottom-up thinker, so my learning process is SLOWWW….

Your email is the first thing I read today and it made me feel good. And when I feel good, I overshare. That might be autism. Or it might be what an autistic person does when safe opportunities to share feel so rare. Or it might be that a diagnostic label like autism only makes sense in a certain system…a system where certain traits that are normally quite adaptive are pathologized. My book is an exploration of the last. It’s a giant footstomp against being told: “Good news. There’s a name for the way you are. It’s a disability. So just throw that name around and people will have to accommodate you.” But I don’t want to be accommodated. I never have.

Oh boy. Here is an early morning rambling I’ll almost certainly spend the rest of the day beating myself up over.

You may know most of my ideas already. I have a hard time guessing how the things I say will be heard…so I either 1) over-hammer points (the way my father would feel the need to explain the history of juice before telling you he’d switched to the newest Five Alive, maybe); or 2) go straight to a level of abstraction that presumes you know everything in my head already (which is how I adjust my behaviour when my over-hammering tendency gets brought to my attention enough times). In any one conversation, you’ll almost certainly get both from me.

Part of the autistic ‘experience’ is is the constant performances, and one of those performances is pretending to know what one’s talking about until one does. This is one of many behavioral patterns that emerge from the struggle to make sense of social models in which you’re presented with a set of rules that no one else seems to really follow. When you follow these rules you’re ridiculed. Don’t be so literal. When you break them you’re punished. You KNEW the rule. Everyone around you navigates this terrain with far less friction. It starts to feel like they have the real rulebook in their back pocket. Unlike others, I can’t seem to ‘let go’ of that friction. It constant agitates me. But on the outside, you perform. And when the majority of your life is a performance, eventually everything you say feels like a lie. But occasionally, a few days or months later, you’ll realize something you said was true. And you’ll be surprised. Very. You realize that these performances have become as much for yourself as they were for others.

_____________________________________

Ugh…here is some more over-hammering.

As I was going through my morning routine, my mind kept going over how these things will be read by the family. Until I have the fullest story I can have, I’ll be purposely vague. But being vague invites all sorts of potential misunderstandings or objections.

My father had a reputation for ruining the few family gatherings he attended. He would bring ugliness. I think those of you who lived through that might be feeling the same about me. He is his father, after all. Here’s this beautiful online family community we’ve created, where we share news of baptisms, memories of loved ones who’ve passed, and other uplifting news…here’s this guy hijacking the group as some sort of platform for his mid-life crisis. I hope no one sees me like that. I’m painfully aware of the impression I can make. It’s this awareness that partly explains my historic lack of participation with family (but I read everything!). Only partly, of course…there isn’t enough time in the day to explain all the reasons I tend to avoid group settings. And none of those reasons are a particular individual, etc.

There are huge elephants in the room that I have to address.

First, I want you to know that I know my father’s behavior was, in many cases, grossly offensive. If you know what I mean by that, then you…already know. His behavior wasn’t harmful only under a certain light, or without a particular understanding…it was harmful, period.

Second, I recognize the very real efforts made by family to help him. What I have to say is in no way a unilateral dismissal of those efforts.

Next (and this is the hardest to address, by far), there are external circumstances of my life (in fact, probably most of the on-paper circumstances of my life) that make anything I have to say very easy to dismiss. I’ve come to understand that a big part of being a ‘high-functioning’ autistic person (i.e. an autistic person with lower support needs) is that you can blend in just enough to do some incredible damage to not only yourself, but others. I have two failed marriages under my belt, and three awesome children who understandably have some very mixed feelings about me. The behaviors I engaged in, the ones I engineered in order to access love and a feeling of belonging, meant making commitments that were well beyond my ability to keep. And if that sounds like self-serving bullshit to you…well, all I can say is that most days that’s what it sounds like to me, as well.

The parallels between my father’s life and my own are tragic to the point of being comical (almost). We’ve both caused damage. I’ve arguably caused more than he did. I functioned ‘better’ and longer. When you’ve caused damage like that, you lose the right to speak. When you open your mouth, people expect sickness. It’s dismissed, wholesale.

So a huge challenge (insurmountable, even) in explaining yourself as a late-diagnosed ‘high-functioning’ autistic person is the very real danger of having everything you say interpreted as self-serving bullshit. After this past year of corresponding with countless other late-diagnosed autistics, I can tell you this is an almost universal experience. The damage is already done. The collapse came too late. You managed to do X, so you sure as hell can do Y like the rest of us. Grow up. All you can do is shrink yourself and hope that the relational debts you (or, more accurately, the persona you created for others) incurred before your diagnosis will be somehow…forgiven? But you know they won’t be. Because you certainlywouldn’t forgive them.

The other challenge is that autism is largely a difference of degree, not of kind. When you try to explain it, people default to their own experiences. Using our own reference points, we assume everyone experiences the world the same way we do. If I were to present my challenges to you in a list, you’d relate to just about all of them. I don’t like loud environments, either. No one does. I have a hard time with hypocrisy, too–who doesn’t? I have a difficult time with change, too. I’ve felt awkward in social situations, who doesn’t? I do best with a routine, everyone does. But life simply isn’t like that. It really sounds like you just want to avoid challenging yourself. It sounds like you’re trying to rationalize avoiding what everyone would like to avoid, but is mature enough to tolerate. Etc. Autistic adults are 7 times more likely to commit suicide than your ‘average’ person. It’s a bit harder to explain stats like that away as laziness or immaturity or irresponsibility.

-

My “Alexithymia” Isn’t What They Say It Is

When I hear that someone is suffering (really suffering, with no way out) it hurts. The destruction of nature hurts. Reading about people in North Korean prison camps hurts. The quiet death of ecosystems, the slow violence of poverty, the stories I read here from other autistic people, the way the powerless get crushed by systems they didn’t create…this kind of pain gets in me and doesn’t leave. It’s like background radiation. I carry it everywhere.

But when someone is suffering because of something they refuse to change, when they clearly could, but don’t…I don’t feel sad. Not really. Not even when I’m supposed to. And apparently that’s a problem. That’s not empathetic, I’m told. That’s cold. That’s…autistic?

So I’ve been thinking: what does “empathy” mean to most people, then? Does it mean feeling what someone else feels, no matter what? Does it mean echoing their distress, even when that distress comes from avoidable choices, repeated again and again?

To me, empathy includes being able to discern what’s really going on, and responding from a place of integrity. Otherwise, don’t we just cheapen words like “sad?”

It’s strange to hear people say I “lack empathy.”What I feel isn’t absence. It’s selectivity. It’s proportional. It’s based on whether the situation actually warrants emotion, not whether I’m expected to emote.

It’s strange how not reacting becomes the problem. Not the incoherence of the situation. Not the person refusing to help themselves. My failure to perform the right emotion at the right time is what gets flagged as a deficit.

And maybe that’s why I’ve also been having such a hard time with the word alexithymia.

Sometimes I look back on an experience…a conflict, a celebration, a goodbye…and only afterward realize it was happy. Or it was unjust. Or it was sad. At the time? I didn’t feel much of anything. I wasn’t there in the way people expect. And I find myself wondering, is that alexithymia? Is that what they mean when they say I can’t identify emotions?

But here’s what I think is actually happening: I wasn’t allowed to be present. I was too busy tracking the expectations in the room. Too busy trying to be appropriate. Too busy masking. The part of me that might have felt joy, or grief, or wonder, wasn’t at the front of the line. It was buried under a survival protocol.

So maybe it’s not that I “lack access” to my emotions. Maybe it’s that I’m not given access to the conditions where those emotions can surface.

Maybe it’s not that I can’t feel. Maybe I’m just too busy surviving.

-

In Relationship with the World

These are some rough-draft ideas from Part I (Feedback Sensitivity in Coherent Systems)

I’ve come to believe that life persists by listening. Not through force, aggression, or even advantage, but through attention to what the world is saying. Everywhere, in every corner of the biosphere, living systems endure by sensing feedback and responding to it. A single-celled microbe navigates chemical gradients; a beaver adjusts the shape of its dam to match the water’s push and pull. Different forms, different scales, same principle: those attuned to feedback persist.

Feedback sensitivity isn’t a marginal skill. It’s not the biological equivalent of knowing how to fold a fitted sheet (nice, but not a prerequisite for survival). Feedback sensitivity is the baseline requirement for survival.

When I say “feedback,” I mean the circular flows of information in a system: a change in one part affects another, and eventually returns to affect its original source. Biologists call these feedback loops “negative” when they put the brakes on change, “positive” when they amplify it. Either way, they provide continuous regulatory information—a live stream of signals that allow an organism or ecosystem assess its own behavior and adjust.

Feedback insensitivity, by contrast, leads to drift: systems that can’t correct, can’t adapt, and eventually disappear. Whether it’s a sparrow or a forest, the more sensitive the system is to these feedback, the more likely it is to maintain integrity, recover from disruption, and thrive in the long term.

Gregory Bateson, systems theorist and anthropologist, observed that adaptive change—which is survival itself—is impossible without feedback loops, whatever the organism or system. Sometimes that change unfolds slowly, filtered through natural selection. But it also happens in real time, as individuals adjust to experience. When I first encountered this idea in Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind, it quietly restructured how I understood learning. Learning, I realized, isn’t something that unfolds in the brain, but in the loop, where it emerges as an effect of feedback. A population adjusting to resource limits, a tree directing its roots toward groundwater—these aren’t acts of isolated intelligence. They’re expressions of relationship: patterns being read, limits encountered, responses being shaped. The adjustment, the learning, isn’t something the organism invents; it emerges through its relationship with the conditions it’s embedded in. Bateson didn’t just theorize this loop; he saw it everywhere: in the way animals communicate, in family dynamics, in evolution, even in his own struggle to reconcile science with meaning.

This learning loop is a universal experience, but for me, as a feedback-sensitive (autistic) person, it feels more immediate, more intense. Of course, that understanding of myself is relational, something that only makes sense as a comparison to other people. And I’ve learned the hard way that this is a very precarious place to argue from. I risk confusion or outright dismissal the moment I try to explain that a sound, a smell, or a minor change is flooding my body with stress, cutting through my thoughts, setting off a physiological alarm. These responses are swift and refuse to be ignored. “Everyone feels that way,” “Nobody likes those things,” or “That’s just life” aren’t helpful words in those moments.

As a child, I didn’t have the words to make my case. I barely do now. But at ten years old, I hardly knew I even had a case to make. One of the most underrated challenges of explaining a difference that’s more about degree than kind is how people default to their own experiences. Using our own reference points, we assume everyone experiences the world the same way we do. If you don’t like loud sounds, and I seem overwhelmed by one, your assumption is that I simply haven’t been exposed to enough noise, or that I’m “too sensitive.” That I just need to get used to it. Try harder. Toughen up. As an adult, I can mitigate these dismissive assumptions, but they still follow me and they still piss me off. As a child, however, the enormous gap between what I felt to be true and what I was told was unbearable. It wasn’t just confusion—it was a minute-to-minute hell I had no words for.

Not every system returns the same kind of feedback. And not every setting collapses the loop. When I was seventeen, and not a little inspired by Thoreau, I spent a summer by a remote lake in eastern Ontario. Not in the off-grid house my grandparents had built, but just across the water, alone in a tent, on a quiet wooded slope that backed onto crown land. I packed everything I needed on my mountain bike and rode the hundred or so kilometers from home in a day. This was my version of Walden Pond. I fished for food, gathered wood for the fire, cleared a small trail. I read. I wrote. I woke with the light, slept with the dark, and moved in rhythm with the weather. There was nothing metaphorical about it—I was in relationship.

There were no social games to decode, no hidden meanings. No buzzing fluorescent lights humming in the ceiling or televisions playing in the background. No sudden shifts in routine. No need for performance. The world around me responded plainly to what I did: when the rain came, I got wet; when I built a fire, I got warm. The system I was inside gave immediate, proportionate feedback. And I adjusted. Not always well. I’m no Thoreau. But faithfully.

I didn’t have a name for it then. But I read Bateson that summer, tucked into a sleeping bag with a headlamp or sitting on the raft at sunrise, and something in his writing gave shape to what I was living.

What I was experiencing was coherence. Not just in the sense of quiet or stability, but in the deeper, systemic sense: pattern integrity. The way things fit together and return information that makes sense. That feedback loop didn’t just regulate me. It affirmed my existence. I wasn’t broken, or too much, or not enough. I was inside a system where responsiveness wasn’t something to suppress; it was a quiet necessity.

That summer changed me…not because it taught me something I didn’t know, but because it stopped contradicting what I already did. My perception, my sensitivity, my reactions, they finally had function. I could feel a difference.

Reading Bateson gave words to a pattern I was already living inside. He writes that when we say some particular organism survives, we’ve already taken a misstep. It isn’t the organism that survives. The real unit of survival, he argued, is organism-plus-environment. I knew what it meant to be part of a system I couldn’t separate myself from. My behavior wasn’t just coming from inside me. It was part of a loop. A reaction to something. A response to conditions.

People like to talk as if we’re separate from our surroundings, as if we’re making decisions in a vacuum. But I’ve never experienced that. When the room shifts, I shift. When the pattern changes, I change. Contrary to what cabin-in-the-woods fantasies would have us believe, life next to a lake is no exception—change is constant, and often requires a response. But those changes didn’t feel like threats or tests. They didn’t throw me into a dysregulated state. I was simply in relationship with what was happening around me. I felt the stability of coherent feedback.

Bateson helped me recognize the shape of my own experience. Here was a loop that I was a part of, rather than trapped within like a caged, disruptive animal, pacing in circles, desperate to make sense of the world outside. He called it a coupled system…two parts shaping and sustaining each other. Not always well. Not always clearly. But inseparably.

We separate the two (organism and environment) because it helps us think more clearly. But it’s only a framework. And frameworks can lie if you forget they’re not the thing itself. It becomes easy, maybe even inevitable, to try to save one part of the system by overriding the other. But that isn’t intelligence. It’s the system misreading its own conditions. “The creature that wins against its environment destroys itself.”

Coherence isn’t a solitary achievement. It’s not just mine, or just yours. What makes life possible emerges from relationship, from one part of a living whole responding to the cues and limits of the other, and adjusting behavior in response to this feedback.

Even at the most fundamental level of physiology, feedback sensitivity is what keeps life stable. Every organism is a dense network of feedback loops, each constantly adjusting temperature, chemistry, and structure to maintain balance, even as the world outside shifts and changes. When my temperature rises, sensors in my brain detect the change, triggering responses like sweating or an increase in blood flow to the skin, cooling me down. A bacterium in a pond does the same, swimming toward nutrients and away from toxins, adjusting in real-time to the environment it encounters. These aren’t metaphors for intelligence—they’re the building blocks of it. Each feedback loop is an expression of life’s most fundamental drive: to stay aligned with the larger pattern.Biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela coined the term autopoiesis to describe how cells sustain themselves through constant feedback. A living cell isn’t just shaped by its environment; it actively engages with it, adjusting its internal chemistry in response to what it perceives. Life, in this sense, is not a static condition, but a never-ending dialogue—an exchange between inside and outside. Fritjof Capra, in The Web of Life, asks us to rethink cognition, not as something locked away in the brain, but as this very dialogue, an ongoing loop of perceiving, responding, and adjusting. Life is that loop. It isn’t just one side of the equation—organism or environment. We use that distinction to frame our sense of self, but really it’s just an abstraction. The truth is, we are the loop. When you say something is alive, what you’re actually describing is its ongoing participation in a dynamic feedback loop. You are not a fixed thing; you are a living, breathing process. An energy flow. And while it sounds ridiculously abstract, it’s the truest way to describe what we usually think of as you. It also happens to be the best explanation for why, for me as a (more) feedback-sensitive person, this fluid sense of self feels more pronounced, an experience of life where that constant adjustment to the world lives much closer to the surface.

-

Fuck “Nature”

“I love nature.”

“I don’t do well in nature.”

“I like nature, but ______.”What the hell do you think nature is, exactly? Why is it reduced to a word? Is it one place among many? Where you bring your dog to take a shit? Where you take a picture of a sunset? What you call “nature” is literally EVERYTHING THAT ISN’T MODERN SOCIETY. That’s a lot to dismiss with a word. It’s 1.3 billion years of life. It’s everything that ever did and ever will provide food, water, and air. Everything you eat, drink, and breathe comes from it.

Nature is REALITY. Swap “nature” with “reality” in everyday conversation, and see the insanity of the modern human paradigm.Wanting to be in reality is a good sign. A signal of health. I’ve been in “nature,” in places that were real, and I am better there. Every organism stands a better chance of thriving in what we call “nature” than in the distortions of modern life. We thrive in reality. Who the hell knew? When and why did we begin thinking otherwise? When did “nature” become something to compare life against? When did we fall for that trick?

Let’s stop rewarding dissociation and calling it resilience.

-

I Can’t Express my Ideas Properly

When I write, I either spend too much time explaining things people already know (which frustrates them) or I say things without explaining them properly (which frustrates them). I can never find find a happy medium.

I’ll try to explain what I mean by “feedback sensitivity.”

When I was diagnosed, I spent months watching the same videos and reading the same books most people watch and read after a late diagnosis. I had the same feelings (probably).

I wanted to know WHAT MY AUTISM WAS. At its core. People say these particular traits are not really autism–they’re co-morbidities. Ok. Let’s put those aside. Therapists say these particular thought / behavior patterns are the result of layered trauma (i.e. decades of being autistic in a “neurotypical” world). Fine. I can see that. Let’s put those aside, as well.

What’s left? What’s at the CORE of this label people give me (autistic/ADHD/OCD/etc.)?

I was left with a pretty short list of what I started to call core traits. Black-and-white thinking, a need for routine and predictability, a need for a certain level of novelty, deep focus, etc.

But lists don’t do much for me. They never have. They taunt the part of me that needs to reason inductively, to find a larger explanatory model. I wanted to know what was common to all of those traits. Where do they come from? What explains them?

(Like anyone would, I applied my own existing knowledge, biases, and frameworks to the task. I’m heavy into permaculture, ecology, evolution, anthropology, and a few other fields. These have always been my “special interests,” as the clinical lingo goes.)

I went down a lot of paths. Some of them were just wrong, and I had to double back. Some led me to the ideas you read about in my book work as it stands, but they sounded different at the time.

They weren’t completely wrong, but they were juvenile or incomplete.For example, I toyed with the idea that I have a DRIVE and a NEED to seek out species-appropriate stimuli and environments (things that are good for humans, in general), and the extent to which I succeed…I’m FINE. The extent to which an environment or stimulus is NOT species-appropriate (not good for people, in general), I’m NOT fine. In fact, the parts of me that were just fine, strengths sometimes, in healthy environments, became disabilities. I still believe this…but I wasn’t happy with “species-appropriate.” Because it didn’t take long for me to realize that what I was talking about were things that were good for ALL forms of life (animals, plants)…not just people.

In the end, what I found to be common to all the traits on my list was: sensitivity. They were all forms of sensitivity. More or less sensitive to change than a neurotypical person. More sensitive to contradiction. To unpredictability. To sounds and smells. Still with the species-appropriate idea firmly in mind, I felt strongly (and still do) that the change I was overly sensitive to wasn’t a level of change that was good for any person…those people were just somehow less sensitive to it. The same went for contradiction. Contradiction doesn’t benefit anyone…it leads to most of the problems we see on the news. The sounds and smells I was “overly” sensitive to? They were the smells and sounds of activities that are harmful to all people (and all living things, really)…engines, synthetic perfumes, etc. So I’m sensitive to harmful things. But shouldn’t I be? Why isn’t everyone else?

I started to think about what allows a living thing succeed in an environment, and what causes it to fail. And I came back to a pretty fundamental principle: an animal succeeds depending on how well it can figure out the rules of a place. The better and faster it can understand the rules of a forest/prairie/pond/etc., and the better it can change its behavior to match those rules, the better it will survive and reproduce.

Break the “rules” of the forest, and you will be “corrected.” Walk through a patch of poison ivy, and you’ll be in discomfort for a week. Go out at the wrong time of day, and you’ll be eaten alive by mosquitoes. These “corrections” the forest is giving you are known as feedback. It’s sort of a strange thing to say because we think of “feedback” as something a person gives to you. Something that’s given to you on purpose. But in ecology, the consequences of your actions in a certain ecosystem are just that: feedback / correction.

So, on the whole, the more sensitive you are to that feedback, the better you’ll survive and reproduce. The better you can read signals and adjust your behavior by them, the more success you’ll have. It’s evolution 101.

With that in mind…I came back to my experience in the world as an autistic person. I’d established (in my mind, anyway) that my level of sensitivity is the right level of sensitivity for a living thing. I didn’t have to come up with hypothetical scenarios to prove this to myself, I spent a lot of my early years at my uncle’s or grandfather’s…remote off-grid places where I just…lived.

But here in this place….I AM dysfunctional. It doesn’t “feel” like I’m dysfunctional, I really am. And it’s that trait, that feedback sensitivity, that is doing the disabling. But that’s ridiculous, isn’t it? How could THE trait most responsible for a living thing’s success lead to disability?

So I tried flipping the narrative. What if it’s the place? What if every single one of my core traits are really just indicators of what’s wrong with this place? “Deep” focus? There’s nothing deep about my focus when I’m in the woods. It’s just focus. “Black-and-white” thinking? In nature? Are you kidding? That’s the only kind of thinking there is. Something is either true or it isn’t

I knew that this wasn’t a very nuanced argument. I knew there were holes. I knew that it was based on my own particular autism, my own particular need for supports, etc.

BUT….core traits, right? CO-morbidities, right? Trauma, right? These are NOT autism. They’re either something that occur with it (they can occur in people who are not autistic) or something that is the result of my “autism,” that core trait of feedback sensitivity, playing for a long time in a very dirty sandbox.

I hope this helps someone, somewhere.

-

My Abyss

My father lived in a dark place most of the time. It was deeply uncomfortable to be around. He’d rant and spiral, consumed by things that felt wrong to him, things he couldn’t let go of. The world became an enemy in his eyes. He raged outward, with a kind of schizophrenic intensity. The air was thick with it.

He would obsess over some perceived injustice or corruption and inflate it beyond recognition. He’d talk about it for weeks. He couldn’t stop. And what might have started from something real would get buried under the weight of his fury. It got ugly. He was ugly. In the end, it looked like nothing but rage…a need to be right.

That’s probably me now.

I feel the same storm building. The same fixation. The same alienation. I walk around already knowing the look people get when they start to back away. I see it. And when I get “like this,” the only thing that’s ever let me forgive myself for being so awful to be around is the belief that what I’m working on matters. That it has to be done. But on the days when I lose hold of that belief, days like today, I just feel monstrous. And ridiculous. A negative force, making everything I touch worse.

What if I’m not fighting the madness I think I am? What if I am the madness? What if this moment, the one where I think I’m beginning to understand, is actually the total loss of my grip on what’s real?

I truly met my father when he was already twenty years older than I am now. I don’t know what he was like at my age. Maybe he was nothing like how I knew him. He might’ve been more functional than I am now. More self-aware. Maybe I’m falling faster. I always have this version of him in my mind…unhinged, over-the-top, shouting…and I swore I wouldn’t become that. But that wasn’t who he always was, was it? Nobody is born like that. He was like me once, believing he still had all the time in the world.

Sometimes I think I’m running the same race he lost.

I’ve spent a lifetime waiting for someone to really see what’s inside me. Not in a vague “I believe in you” kind of way, but someone with the understanding and the means to give me time. Breathing room. A protected space to develop the thing that keeps flickering inside me. Not a free ride. Not praise. Just time. Space. It’s a childish fantasy. I know that. But I’ve spent a lifetime waiting for those people anyway.

And some days I’m sure there is no such person. That I’m in a world of one, like my father, and that my ideas only make sense there. Only make sense to me.

Today, I feel rage. Toward myself. Toward the world. I’m disgusted with how seriously I take myself. But I’m still angry at everyone else for not taking seriously the things I see. People mowing 40 million acres of lawn, stupid or demented…I honestly don’t know which. As if nothing ever gets through. A mirror has been held up a million times, a much better mirror than I could ever hold up, and they just keep brushing their hair in front of it.

Confusingly, I feel a lot of rage toward autistic people online. I’m ashamed and embarrassed to admit this, but I feel abandoned. I pour myself into something, try to name what I think we‘re really feeling…something deeper than just day-to-day frustration or sensory overload…and I watch it get buried. No replies. No spark of recognition. Just more talk about dating and work anxiety and video games. Or I get torn apart. “So you’re saying [strawman argument]” (followed by 37 replies equally outraged by that particular false interpretation of my thoughts). I feel rage, not because I don’t care about them, but because I need someone to say, this is it. This is what I’ve been trying to say, too.

Instead, I feel like a freak. Screaming into a void.

It makes me feel ridiculous. Like maybe this is just a blown-out-of-proportion hyperfixation, after all. Like maybe all of this…the thinking, the writing, the physical stress…is just some “autistic loop” with an inflated sense of importance. And I feel so, so ugly. For my parents. For my partner. For anyone close. And I wonder, no I scream…WHAT IS IT ALL FOR?! What exactly do I think I’ve earned? What exactly do I think I deserve?

Because by society’s standards, I’ve gotten exactly what I deserve. Nothing more. Nothing less. And everything I gave…every piece of myself I tore out and offered…it looks like less than nothing. Just another strange, intense person with grandiose ideas and no ground beneath them.

Sometimes I think I’m brilliant. But I also think I’m trivial. Laughable. I don’t trust my reality. Not at all. I keep waiting for confirmation. Not from a crowd. Just from someone. Someone who can say, without hesitation, you’re not insane.

Because I’m fucking terrified.

Not that I’ll fail, but that I’ll become twisted beyond recognition long before I can save myself. That I’ll lose the thread entirely and end up in some permanent shape the world finds repulsive or sad or best hidden. And that the world will come for me. That it will come for my masks. For debts owed. What will those people find? Something unable to defend itself. Unable to explain itself.

I don’t want to be that.

I don’t want to be alone in that.

I want someone to see me, not as a burden, not as a cautionary tale like my father, but as someone worth helping before it’s too late.

And I don’t even know if that’s possible. -

Overstimulated by Bullshit

I’m working on a section that explores neurodivergence and artificial reward systems. I’m looking at how modern society’s “treats” affect neurodivergent people…especially compared to neurotypical peers, who function as a control group.

You just don’t want to shower.

You just don’t want to stop drinking.

You just want to scroll, play video games, snack, sleep in, give up.

You don’t want responsibility. You want excuses.

You’re not “neurodivergent.” You’re just impulsive. Lazy. Weak.

Grow up.That’s by far the loudest voice in my head.

For years, I’ve tried to hide the fact that I can’t tolerate environments, stimuli, contradictions, etc. that others seem fine with. But I’ve also had to hide what seems to be an inability to resist what others do. I can’t have games on my phone without playing them excessively. I can’t have junk food in the house without eating myself sick. So I don’t have either. I have to keep the phone game-free and the fridge can only have whole foods. It’s embarrassing to admit. And this feeling isn’t a hindsight sort of thing. I feel it RIGHT NOW. Being overwhelmed by modern society’s excesses will probably ALWAYS feel like a personal moral failure to me (no matter how I tell myself it might be something else.

What makes me special? Why wouldn’t people assume when I say I’m autistic or ADHD, that I’m trying to cash in on some behavior lottery…one that gets me out of doing things no one really wants to do, and grants me freedom to do whatever the hell I want?

If that’s how you see me, “Nice try, asshole,” is probably the correct response.

My own particular mask doesn’t help…the one I’ve worn most for the past ten years or so. It could best be described as “interesting redneck.” A bit of me peeked out, of course. The permaculture methods I like to use on my property. The odd opinion I shared…on how nice it was to have deer in my fields again (during Covid lockdowns), for example. Or repeating (a little too often) how grating the sound of the increased traffic on my road is. But by and large, I masked as what you would expect to find in a middle-aged man in a rural area. Work hard, play hard, don’t give me excuses, and all that bullshit.

My diagnosis was like a chair to the head for that mask. None of the literature I was reading, none of the data I was seeing, could possibly allow it to survive. It didn’t just get heavy…it was putrid. It reeked of stupidity, and I knew I’d never be able to pick it up again, let alone put it on. The same proved to be true of all my masks. The studies, books, and data exposed them all for what they were.

I’d convinced myself, but how can I convince others? Put aside the fact that I’ve never been good at that. Let’s say, for a moment, that I was somehow able to articulate myself in a way that would cause people to listen. Well, even if I managed to quell the straw-man argument hell I was opening myself to (“What the hell are you on about? My 5-year-old autistic son has yet to speak a word. He needs help getting dressed. And you’re trying to sell me the idea that autism is some sort of biological advantage? Fuck you.”), anyone with an (indoctrinated) brain in their head isn’t going to listen to me then explain how me not taking a shower or having a beer at 9 in the morning might not purely be a personal failing. These are big bloody obstacles. The feedback I got from the few people I shared my ideas with was nothing but confirmation.

I knew I would need an insurmountable amount of data to even have the slimmest chance of reaching a mere fraction of the most open-minded readers.

I found it.

I didn’t just find it…I found it with ease. (The comparative studies are everywhere. Meta-analyses. National surveys. Neuroimaging. Behavior data. It’s not subtle.)

It needed minimal organization. It formed its own framework. And for someone like me, that’s….sheer ecstasy. An explanatory model that not only survived months of scrutiny, but instantly encompassed my hunches, my experiences, and my conclusions? How often does that happen, really? I’m a bottom-up thinker, an inductive thinker, my very nature precludes the possibility of cherry-picking data for a theory, no matter how attached I am to it. Devil’s advocate isn’t one voice among many in my head…it is the voice. I can’t “let things go.” That isn’t a flex…it’s just the way I am (and gets me into all sorts of shit). But this research was turnkey. It formed its own coherent argument. One that made me physically excited. Happy dance-flushed-stimmy excited.

I’ve known for a long time that modern civilization doesn’t run on real signals. It runs on engineered superstimuli—“food” that’s sweeter than food, screens that flicker faster than your brain evolved to track, validation loops designed to mimic love, stimulation, and safety. In 2025, everyone knows that, really. It’s common knowledge—almost trite. And for most people, not a minority, these things are hard to resist. But for some of us, it borders on impossible.

My experience isn’t a story of addiction or lack of willpower. It’s a story about susceptibility. The susceptibility of a feedback-sensitive brain to systems that were built to extract something from it. Clicks. Likes. Data. Energy. Money.

Let’s be clear: not all of this is about chasing pleasure. Sometimes, it comes from avoiding pain. The sensory chaos of a grocery store. The moral incoherence of workplace small talk. The emotional friction of living in a world that doesn’t return clean, proportionate feedback. Many neurodivergent people withdraw from that world…not because we’re lazy or disinterested, but because it costs too much (neurologically) to stay in it. But withdrawal comes with its own costs. You’re not going to the farmer’s market. You’re not joining the running club. You’re not cooking a family meal. But you seek what you need (quiet, stimulation, reward) somewhere. And modern society is more than happy to offer it: in bags, in bottles, on screens.

Still, that’s not the core argument here. Avoidance doesn’t explain how precisely these systems seem to exploit my wiring.

This isn’t just about being boxed in by circumstance. It’s about how the system itself is built. It’s about the intensity of the signals, the distortion of natural feedback, the way those signals strike differently in the more sensitive among us. It’s about the fact that even when the external stressors are removed, the engineered signals often still hit harder, register deeper, and dysregulate faster.

It’s about what happens when a feedback-sensitive person is exposed to artificial reward systems.

Do you know what happens?

When the signals get too loud for a feedback-sensitive brain to filter or resist?

28% of adults with ADHD are obese. That’s not about chips being available. That’s about chips being formulated…saltier, fattier, more dopamine-releasing than anything in the ancestral record. The average? Sixteen percent. This is a feedback-sensitive brain lighting up “more,” doing its job. It doesn’t let go.

Children with autism? 41-58% more likely to be obese than neurotypical peers. Are they less able to comprehend what is healthy? Do they have less willpower? Are their parents less caring or strict? Or is it because engineered food is built to override satiety? To turn feedback sensitivity against itself?

25-37% of teens with ADHD meet clinical criteria for internet gaming disorder. Not “likes games.” Disorder. Autistic children? 3.3 hours of screen use vs 0.9 hours/day for neurotypical peers. Autistic adults? Statistically higher scores on gaming addiction tests (9% higher than clinical thresholds). Why? Structured environments. Rules. Possibility of mastery. Variable-ratio reward schedules. Sensory immersion. Linear feedback. It’s everything a feedback-hungry person wants. These are conditions they are starving for…rarely present in that place we now call the real world.

Social media hits harder too. Each like, each comment, each notification…engineered to simulate social connection. For ADHD, it becomes a loop. For autism, it becomes a need. These are two sides of the feedback-sensitive coin. Both are pulled deeper, faster, and stay longer.

Pornography? Another biological drive hacked: reproduction, bonding, pleasure. But louder. Faster. On-demand. Zero ambiguity. Anyone might get addicted. But for ADHD brains (for a feedback-sensitive person living in a system that lacks biologically-significant novelty), it’s dopamine on tap. For some autistic people (feedback sensitivity in a system that’s full of distorted signals and contradiction), it becomes a ritual. Not because of what it is, necessarily (pornography), but because of how it behaves as a signal.

Substances? The brakes and accelerators we use to reshape society’s feedback into something comprehensible, or at least dull it? 23% of people with ADHD have a co-occurring SUD. Autistic adults are nearly 9 times more likely to use recreational drugs to cope with the consequences of distorted feedback (anxiety, sensory overload).

Compulsive shopping, binge-watching, substance abuse, overuse of screens: same pattern. Not lack of restraint. Not moral decay. Signal distortion.

These systems engineer signals based on how the human brain picks up and processes information. They’re not bloody well accidental. They’re designed to strike the nervous system where it’s most receptive. They’re practically a case study in human feedback-sensitivity (funded by consumer / tax dollars).

The more sensitive the person is to feedback, the better these signals “work.” It isn’t complicated. So why? Why is it contentious to say these things? Why, despite everything, do labels of dysfunction continue to accumulate on this side of the equation?

At this rate, we’ll need to expand the English language. The words don’t exist yet for the number of labels we’ll need. Because this is the gradual pathologization of life itself.

-

Transitions SHOULD be hard (in this place)

I’ve had a problem with transitions my whole life. Bed to shower, shower to kitchen, reading to greeting guests, greeting guests to mowing the lawn…it’s always a fucking battle with myself. When I was diagnosed, I was told what I already knew: “You’re bad with transitions.” You overreact (I do). You shut down, or get stuck, or blow up at things that seem easy for everyone else (I do). I was given new words. Cognitive inflexibility. Behavioral rigidity. Insistence on sameness. Resistance to change. Perseverative behavior. Pathological demand avoidance. Dependence. Delay. Resistance. Slow. Poor. Intolerance. Difficulty. Rigid. Distress. Impaired.

OK, so I’m clearly not cut out for life.

But is it life?

In a coherent system, the one we evolved in, transitions aren’t hard. Not because organisms there are tougher or more flexible, but because the transitions themselves make sense. They’re part of that system. Seasonal shifts. Puberty. Grief. Rest. They don’t happen suddenly or without warning. They come with cues. Physical cues. Environmental cues. Even social cues.

Here’s the thing: organisms from those systems don’t “adapt” to the timing of transitions. They’re formed by them. There’s no gap between the system and the self. The rhythm outside becomes the rhythm inside. I don’t just endure spring. Don’t be ridiculous. I become the kind of creature that responds to spring. I don’t “handle” hunger. I become hungry. In a place that makes sense, that leads to finding or growing food. The feeling arises with purpose, and the transition it asks of me (movement, focus, effort) is supported by everything around me. I’m doing what I’m meant to, when I’m meant to.

That’s what real feedback does. It shapes you as it informs you. And when something in the environment changes (something biologically real) a feedback-sensitive person picks that up fast. They change in response. And they change quickly, and they change well. In step with what’s actually happening.

That’s feedback sensitivity: the degree to which your behavior maps to signal. That’s what makes an organism adaptive. That’s what makes a person adaptive. Not just quick to change, but able to change in a way that fits what’s real.

It’s not a side trait or a quirk. It’s the foundational condition beneath every other trait we call adaptive. Learning? Downstream. Flexibility? Downstream. Even thought (real thought) starts with the ability to pick up on what’s true, and respond.

That’s what makes it so fucking painful to live in a system where most signals don’t mean anything.

Modern civilization is full of transitions, but they aren’t tied to any real need. They aren’t about my body, or the land, or the seasons. They’re constructed. I move from one grade to another. One job to another. One building, platform, device, account to another. One activity of questionable importance to another. It’s not that my life changes…it’s this weird environment demanding I act as if it has.

I try to keep up. Because I’m still wired for signal. I still think transitions mean something. But they don’t anymore. They’re non-referential. They point to nothing. They’re fast, constant, and nearly always disconnected from any ecological pattern or how ready I am. And the more I try to track them, the more exhausted I get. Because I’m not supposed to track that kind of noise. I was never meant to.

Modern civilization doesn’t create real transitions. It just repartitions reality…chops it into convenient segments that suit its own internal logic. It rearranges things for the sake of efficiency, not coherence. It runs on deadlines, not seasons. Bureaucracy, not biology. And when its logic starts to fail (it usually does) it doesn’t get corrected by feedback. It distorts or severs the feedback loops that would normally force it to change. So that I get corrected. I get labeled.

It builds itself on top of the coherent system (the real one: biological reality)…but increasingly in defiance of it.

And then it calls me broken when I struggle.

But let’s be honest: struggling to move from one meaningless task to another, from one harmful environment to another, should be difficult. Struggling to shift from something that matters to something that doesn’t…that should be hard. If it’s not, that’s not a sign of health. That’s a sign that something inside has gone quiet. That feedback sensitivity (the thing that tells you what fits, what hurts, what’s true) has been pushed down so many times it stops trying to speak.

We live in a place that celebrates that. It calls it resilience. Social intelligence. Professionalism. Maturity. But more often than not, it’s just the absence of protest. A learned silence.

Here’s a deeper layer: over time, humans selected themselves for exactly that. Not for sensitivity to truth, but for compliance. For docility. For the ability to tolerate contradiction without protest. That’s self-domestication. It’s what lets people smile while a system collapses around them. What lets them adapt to noise, to simulation, to systems that reward pretending more than perceiving.

And that’s not a knock on anyone…it’s just what systems like this select for. If I can’t seem to get on board with that, I’m pathologized. Called inflexible. Dramatic. Disordered. And those are all accurate descriptions of me in places like that.

But is difficulty with incoherence really dysfunction? Isn’t it the thread of something real?

I can handle change. I can’t ignore when a change isn’t grounded in reality. When a signal doesn’t match a truth. When the transition isn’t tied to anything that matters. My whole system lights up. I think maybe it’s supposed to.

Recent Posts

- Survival Stories

- Fidelity to the Group Vs Fidelity to Reality (blue pill vs red pill)

- Scarcity -> Conflict

- WILL

- No…autistic people are not rigid thinkers.

- What IS domestication?

- Where does the real control begin? (How did we get from egalitarianism to building permits and marriage licenses?)

- Domestications V1.0 / V2.0 (hunter-gatherers / suburbanites)

- Why Wrangham’s Hypothesis is Hobbesian (again)

- Was Hobbes right? (and other holes in Wrangham’s narrative)

- Human Self-Domestication…selection against autonomy, not hot heads.

- Different Maps of Reality

- ramble (predictive coding, autism,simulation)

- The Cost of Food = A Seed

- “The Dark Ages” (a civilizational propaganda campaign)

- The sooner civilization collapses, the better.

- Tribalism, Consensus Reality, and Domestication

- What Wrangham Gets Wrong About Human Domestication

- I’m sorry.

- The Predictive Brain: Autistic Edition (or Maybe the Model’s the Problem)

- Social deficit? Or social defi…nitely-don’t-care?

- Human self-domestication, Pathological Demand Avoidance, and “self-control” walk into a bar…

- Domestication and the Warping of Sexual Dimorphism

- Domestication at the Top (When Wolves Build Kennels)

- The Great Culling: How Civilization Engineered the Modern Male

- The Genome in Chains

- Human Self-Domestication–Passive Drift or Violent Control?

- So what is “neurodivergence,” really?

- The Domesticated vs. The Wild

- Compliance vs. Resilence (to Incoherence)

- Is there such thing as a “baseline human?”

- The Civilizing Process IS Domestication

- What’s the “civilizing process,” really?

- Feedback Inversion

- What is “neurotypical” across living systems?

- The Double-Empathy Struggle

- No…autistic people don’t struggle with complexity.

- Is compounding error to blame?

- Is technology to blame?

- Is abstraction to blame?

- Stability Versus “Progress”

- Is civilization inevitable?

- Never-Ending Conflict

- Dominoes

- Nothing

- I Have Nothing of Value to Say

- Premises

- No Feedback = Dominance Hierarchy

- Civilization as a Process

- I’m “divergent” from WHAT, exactly?

- What We Did to the Dog

- Life as Pathology

- Letters to Family after a Late Autism Diagnosis

- My “Alexithymia” Isn’t What They Say It Is

- In Relationship with the World

- Fuck “Nature”

- I Can’t Express my Ideas Properly

- My Abyss

- Overstimulated by Bullshit

- Transitions SHOULD be hard (in this place)

- Masking: The Feedback That Lies Back

- The “Rise of Autism”: Diagnostic Inflation